Cornwall & SW Fruit Focus (8) ‘Past experience – future knowledge’ Eden Project Core Suit Saturday 19th March 10 am – 5 pm

Cornwall & SW Fruit Focus (8) ‘Past experience – future knowledge’ Eden Project Core Suit Saturday 19th March 10 am – 5 pm

Andrew Lea had a distinguished career at Long Ashton and Cadbury Schweppes as a biochemist. He was at Long Ashton for 13 years in the 70’s and early 80’s which is where he learnt about cider making, which he was able to pursue later.

He is well known and well regarded by craft cider makers from his book ‘Craft Cider Making” and from his web site The Wittenham Hill Cider Portal http://www.cider.org.uk

Andrew’s talk looked at the progression of cider making over quite a long time span.

Cider making in the beginning.

Among the earliest records were from Strabo a Greek traveller in Asturias in the first century AD but it isn’t clear if this referred to beer or cider. The Roman naturalist and historian Pliny 79 AD definitely wrote about the preparation of wine from apples and pears. He even quoted the Falernian as the best pear variety to make perry. There is a decree apparently by Charlemagne in the 9th century that all estates should grow fruit and make cider. In Britain there are documentary records from about 1200 onwards and it increases over the years after that. There is no evidence of any UK cider making before the Norman period. The Anglo Saxon period didn’t appear to have any cider making. There is no documentary evidence to show that when Julius Caesar arrived he found the native Celts drinking cider (which is constantly re-hashed in all the books!).

Words for cider are interesting

Apparently it comes from a Hebrew word síkera, which means fermented liquor, strong drink (it could have been associated with palm wine). It became adopted in Medieval Latin as sīcera, Middle English cidre or sidre, from Old French cisdre or sidre English, French and Spanish word are based on these origins. In the German-speaking world it is just apple wine but there are other dialect words that they also use. One of the interesting words they use in the Mosel is Viez. From the Latin “Vice-vinum” or “substitute wine”. (Like Vice chairman is a substitute for the chairman).

How far back does written documentation in making cider go?

The furthest back is a book written in 1589 by a Norman Julien Le Paulmier originally written in Latin “De Vino et Pomaceo” and translated the following year into French as it was likely to have been popular. He worked in Normandy and a lot of it is about cider making and how to make cider. To put it into context Shakespeare’s Richard III is 1592. There are several British books following in the 17th century by Ralph Austen, John Evelyn and John Worlidge’s ‘Treatise on Cider’. Those writers were not in what we now think of as the traditional cider making areas. Ralph Austen was in Oxford, Evelyn was in Dartford in Kent, a very unprepossessing area for making cider now but he did grow and make cider there himself, Worlidge was in Sussex. Even then they recognised the West Country was the best place to grow cider apples and produce cider. By the 18th and beginning of the 19th century the focus had shifted to the West Country. Thomas Andrew Knight (Herefordshire) who was the first chairman of the RHS was very interested in cider production and fruit trees and his book went through 5 editions and set the scene for modern cider making after that. He was one of the first to introduce the hydrometer to measure the sugar in the juice to work out the amount of alcohol you were going to get in the final cider. From the frontispiece of Worlidge’s book – this mill was something that Worlidge designed so was new technology at the time. It was based on a Cuban sugar mill. It was two contra rotating rollers originally designed to crush sugar cane – and Worlidge realised it could be used with apples. It was the beginning of the technology associated with cider making. In the 19th century there was a rush of books not only English books but also in the USA where cider was beginning to be important. Towards the end of the 19th century we end up with some important books Hogg and Bull, “Apple and Pears as Vintage Fruits” which describe a whole range of British Cider varieties and the way you could use them. Radcliffe Cook wrote “A Book about Cider and Perry” he was MP from Hereford and was always pushing cider in the House of Commons (to some peoples annoyance). William Alwood an American came over to Britain Germany and France because he wanted to have a good idea of how we were making cider to improve the American cider industry. He published a review “A study of Cider making in France, Germany and England’ in 1903. He wasn’t complimentary about how we made cider and he was far more complimentary about the Germans.

It is in the 1890’s when industrial cider making is beginning to diverge from craft cider making. Prior to that there wasn’t any distinction, as cider was made very locally on individual farms. It was drunk by agricultural labourers, possibly by the gentry if made more carefully. It was consumed within a very local area. The arrival of the railways allowed cider to go to far distant places, in which case it had to be more competently made. That is when industrial cider making started to diverge.

The Bath and West Society was getting very interested in Cider quality (or no cider quality as they saw it). They set up a series of trials. It brought together a lot of scientific information about cider making for the first time. That led to the formation of the Long Ashton Research Station set up in 1903 originally and solely as a cider research institute. It rapidly became a major horticultural research institute in its own right and cider became less and less important – the cider section for which I worked closed in 1985. The whole research station didn’t close until 2003 so it had a hundred year history. Most of the promotion and teaching cider making was done through courses and research rather than manuals and great books. Long Ashton published only two books on cider making. Vernon Charley ‘Principles and Practices of cider making’ was based on a translation of a French volume updated to British practice. Charley worked at Long Ashton in the 1930’s where he invented Ribena. By the time he published his book on cider making he was already at Carter’s at Coleford in the Forest of Dean. Which later became Beecham’s which later became GSK and is now Suntory. The site is still there and they still make Ribena on site. He diverged away from cider by that time. Beech and Pollard published a book for small makers in 1957 otherwise most of the information was published in scientific journals or annual reports.

By the 1970’s when I was there big companies were doing their own research and development. And moving away from what Long Ashton was able to provide. They continued to be interested in the pomology side because that was seen as pre-competitive. All the companies could come together and agree on what they could do. The cider making per se tended to be more competitive so firms did research on their own.

Late 20th/21st Century

Many new books from North America and Andrew Lea’s own book was published. There is a greater amount of information about cider making on the Internet of varying quality.

Different types of apple trees.

If you look through the history you might think the same types have been used over time. Although there are named varieties in those early works, very few persist to the present day in an incontrovertible form. Probably the only ones that do are the Foxwhelp group of apples, which are bitter sharps, Foxwhelp is still with us and still grown. There are two 19th century Pomonas where apples were written down and recorded – Knights from 1811 and Hogg and Bull from 1885. Quite a lot of cider apples they list are no longer available and if they have been rediscovered there is some doubt about their provenance. So we may not have that link to the past anymore. There is a group in Hereford called the Woolhope Club, which is a natural history society they were keen on rejuvenating cider varieties in the 19th century. They went over to Normandy deliberately to import varieties to improve the stock that we had in the UK. One of the French ones still widely grown today is Michelin. Many people including Knight thought that fruit trees had a natural life span. They thought varieties would weaken decay and that would be the end of them. We are clear that is not true – when it is true it is due to viruses. The trees were virused and the viruses were propagated in the scions. Once you clean them up from viruses you can go back to healthy trees again. That was unknown at the time – so there was a quest for new varieties all along – to replace old varieties that were dying off.

Modern cider apple classification 1905

There are four types, bitter sharp, bitter sweet, sharp and sweet. They are distinguished by their tannin and acid levels. You need a blend of all those for a palatable cider – hence why blending is the cider makers art. There was an additional overarching category – vintage quality – difficult to analyse – certain apples are better for cider making because of depth, complexity and interest. Long Ashton produced a list of vintage quality apples. So if you were going to plant a cider orchard with no other constraints those are the things you would look at.

Vintage and Bulk Cider apples.

The difference between a craft producer and an industrial producer is that the craft producer will have more vintage types in his blend as they are more difficult to grow, often more pest and disease prone and lower yielding, odd angles, more difficult to train. They typically have low nitrogen uptake from the soil. Nitrogen uptake will be lower hence fermentation speed will be lower. They generally are believed to have an improvement on quality if you are a small-scale craft producer. Many of the varieties we now work with including the vintage ones are quite modern. Many are seedlings from the late 19th century. The older ones fell into disuse and no one was propagating them. New ones came along and they were normally seedlings or chance discoveries. People said this is good we will propagate this and continue this. So well known varieties such as Dabinett, Harry Master’s Jersey, Yarlington Mill were all seedlings from South Somerset that were recognised as being worth keeping going and now form the basis of the industry. More modern Pomonas have been produced Bulmer’s in 1985; Liz Copas the last Pomologist at Long Ashton has produced a cider Pomona which has been updated recently. Charles Martell has produced Pomona of Gloucestershire apples including many cider varieties.

Changes in orchard management

Low-density standard orchards (30 trees per acre) grazed by animals were superseded by bush orchards (300 per acre) from the late 1930’s. They didn’t get into their stride for cider until the late 1960’s – 1970’s. Bulmers, Showerings and others started to plant up large acreages, mostly on MM106 rootstocks but sometimes-using MM111 and M26 rootstocks. They are managed for intensive production. There has been more recent experimental work using M9 on much more intensive hedgerow wall type systems. Whether they will take off with the bulk of producers I am not sure. 45% of all UK apples are grown specifically for cider. The UK is unusual in growing a large proportion of apples specifically for cider and no other purpose.

Mechanical harvesting was developed to accompany bush orchards, unlike dessert fruit, which are harvested from the trees themselves. The debate about mechanical harvesting of dessert fruit is still not solved. For cider that is not an issue as the fruit are dropped on the ground anyway (either naturally or mechanically shaken off the trees) and the fruit are swept up from the ground (in traditional and bush orchards).

Cultivars available

Craft producers have a lot more cultivars available. There are local varieties for instance in Dorset and Cornwall that never got into the canon of varieties codified at Long Ashton. Samples were never submitted so were outside the net. These are now being rediscovered and looked at which is of interest to many people. The season of use for traditional varieties can be quite wide ranging from Bitter Sweet Nehou which is ready in August, and Vilberie also a bitter sweet that is ready in December. It may not matter if they go biennial – if some go biennial – others aren’t. However, often in one area all the apples will go ‘in phase’ due to climatic factors. Craft users are not particularly bothered about getting maximum yield. If you are an industrial producer you have different constraints. You have to have a good supply of fruit that is well managed and isn’t going to let you down at the last moment. Michelin and Dabinett are the workhorses of cider production because they are reliable bittersweet varieties which suffer less from biennialism and you can’t get these characteristics other than from cider apples. You can get as much Chinese concentrate as you like but it isn’t going to have the tannin or other qualities that you would get in a British cider apple.

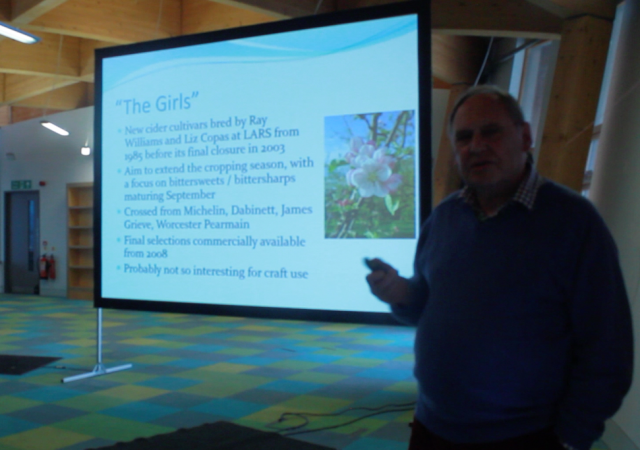

The problem is peak crop coming in a small window October/November and that was one for developing a new set of cider apples. Liz Copas was involved in developing these with Ray Williams at Long Aston between 1985 and 2003. Called ‘the girls’, because they were named after various women who had been involved in the cider apple industry with a few exceptions. These include ‘Prince William’ – who in his youth admitted liking a glass of cider and ‘Willy’ named after Ray Williams who instigated the program. The aim was to extend the cropping season allowing the cider mills to come into production earlier in September, which was of value as it spread the processing season. They used Michelin, Dabinett, James Grieve and Worcester and produced 1000’s of seedlings, which were gradually whittled down. The last selections became commercial in 2008. They aren’t so interesting for craft use as they were selected on the basis of early cropping. They probably don’t have vintage quality but they haven’t been around long enough for us to know. In due course we will know how they respond in the long term.

The Girls have been classified into different usage groups, bitter sweet, bitter sharp, sweet and a group for straight juicing.

What happens in other countries?

We normally think about Britain and France in terms of cider but other countries in Europe such as Germany and Spain have a substantial cider industry. The markets that have suddenly developed recently include the US and Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Canada/USA

The new world has become a new cider market and production area.

Its history goes back a long way Connecticut cider goes back to 1664 producing cider in the colonies at that time. As they have been producing for so long they do have some pre-colonial cider varieties. These aren’t used much now except by the specialist makers. Thomas Jefferson was 3rd US President and one of the authors of the Declaration of Independence. He had a large estate in Monticello in Virginia and he was interested in horticulture and fruit growing. He had a variety that he waxed lyrically about called the Taliferro which seems to have been lost after Jefferson’s death and Tom Burford the sleuth of old US apple varieties has been unable to find it. What some US and Canadian growers are doing is producing fruit from British and European varieties. So they have taken a lot of English and French varieties and are trying them out as well. Success depends on climate in the Pacific North Western strip from Canada down to Oregon you can grow apples almost like in the UK. Take them to the mid west, Michigan or to the North East where it is a lot colder, they often can’t stand the climatic extremes. Most US craft cider because of the lack of fruit is made from pack house rejects. The difference between the New World and ours is that every two weeks the pack house is opened, fruit is taken out and regraded. All the chuck outs are going to juice or outside the industry the rest goes to the dessert market. So their cider will be made from Gala, Fuji, Red Delicious, apples we wouldn’t consider for cider making in the UK – but that is all they have got. Even craft producers producing full juice cider have little else to work with. The products are quite sweet to our way of thinking and usually carbonated. You don’t get still draft cider as in the UK.

Australia/New Zealand

Similar story – Granny Smith originated in Australia and used in their cider blends. They don’t have their own cider varieties but they have some English and French introduced prior to plant quarantine restrictions in collections. There is a good collection in Tasmania originating from some Bulmer’s work trying to set up an Australian cider industry as an offshoot of the UK industry. They imported UK varieties although that work never continued. The craft cider industry is using Bulmer’s material that has been repropagated. There can be problems as the climate is different other than Tasmania which has a relatively cool climate.

Temperatures in South of Australia are very warm producing very high sugar levels with alcohol levels going up to 11%, which is an apple wine. It is a very different proposition based on natural sugar levels in apples. Winters aren’t cold enough (which cider apples need) so fruit set is very poor. So they struggle with European cider apples – typically they use apples coming out of controlled temperature store in pack houses diverted to cider. Many Australian cider makers started as wine makers – they diversified, as the wine industry needs to diversify. They use winemaking technology and have fermentation tanks that can be cooled right down. When fermentation is partly completed they undertake “cold crashing”. Cold glycol is pumped around the outside walls of the chiller tank. Temperature drops down and fermentation stops pretty well, they rack the juice off. They put it through a cross flow filter to capture the cider with some residual sugar in it, ready for packaging They have a relatively low alcohol high sugar product.

How to define craft cider making.

In the UK craft cider is made from full juice 85-100% juice in the cider. Many commercial producers use 35-50% juice the rest is fermented glucose syrup. That is why the flavour is quite light in many modern commercial ciders compared to craft cider. In addition craft cider makers use fresh juice rather than apple juice concentrate, which is a component of larger scale cider producers cider making. A lot of the technologies both sides of the industry would be using.

Development of craft technology – Development over the years.

Mills have changed from scratters to knife mills. Presses changed from straw to cloth to hydraulic bladders. Wood and fibreglass are out and replaced by plastic and stainless steel.

Clarification .

Most craft cider makers aren’t concerned about this those who are use sheet filters

Storage (bulk dispense) containers have changed

This has evolved from wooden cask to plastic poly cask and now bag in the box, which has a tremendous advantage in terms of stopping oxidation.

Quality control of the fermentation process

Now craft cider makers are more interested in knowing more about sulphur dioxide, different forms of yeast, malolactic fermentation to control flavour and acidity.

Traditional mills and presses.

Traditional processes have evolved from horse mill, via scratter roller mills with teeth to pulp apples that drop down through the rollers. Modern mills have stainless steel knife, such as the compact electric Speidel mill. Craft scale presses haven’t changed very much over time. Originally layers of apple were layered up between layers of straw to make a ‘cheese’. Straw has been replaced by cloths supported by wooden slatted racks. This process is not very different than the Austrian Voran Press sold very widely throughout Europe.

The hydro press is a slightly different design. It consists of a rubber bladder with a cage outside. You fill pulp between the two, the bladder is filled with water under pressure it expands and squeezes the juice out of the fruit. The outer cage is covered with a filter. It is a German design and has become popular recently with small-scale producers; there are big scale versions of the same thing.

Modern craft fermenters

Purpose built wine cider fermenters and a special kind of stainless steel tank are now used. One of the most important things is to keep the air out when the cider is finished; otherwise cider can rapidly oxidize and produce unpleasant flavours. Variable capacity tank has been developed– the lid floats up and down on top of the cider. A floating lid means there is no risk of air coming in contact with the cider. There is an inflatable bicycle tyre around the rim to keep the lid in place. This is a modern piece of technology to keep the air out of the cider a key point of cider making.

Yeast choice

One of the developments in brewing and cider making has been the use of defined yeast cultures to produce uniformity of production and flavour. Cultivated yeast is very uniform, wild yeast very variable.

Bag in box dispenser.

Originally invented in Australia for dispensing wine with a flexible bladder in a cardboard case – the flexible bag draws around the liquid letting no air in allowing it to keep for several months unlike the wooden or poly barrel where air is drawn in as the barrel is emptied.

What’s Next for UK Craft Cider Making?

I suspect many things will stay the same. There is always a strong connection between the grower and the cider maker. They are either the same person or they grow in the same area The cider maker will know a lot about where the cider is coming from.

We have a lot of vintage varieties in the craft cider industry and I don’t know if we need any more, it is a case of choosing them more intelligently. Having a blend of known quality apples helps with marketing and getting into peoples minds.

The effect of climate change is a difficult one the NACM has done a review of the impact in relation to cider. There are worries in relation to winter chill, flooding, diseases such as fire blight, high winds (apple walls can be blown over for example). These are unknowns.

I suspect the new cider apple varieties – ‘The Girls’ will not make a big impact on the craft maker. There will be more interest in knowledge about yeast and bacteria cultures. As far as technology, a lot of what people do depends on the cost and economic benefit this will determine if they decide on a pack press, belt press or hydro press – this isn’t going to change. Plastic and stainless steel fermentation vessels seem to be the norm. Wood if used is for the maturation phase – not for cider making as this is difficult to control.

There is a new technique called ‘cross flow filtration’ which has completely revolutionized main stream cider making and the cost is dropping to the point that it is affordable by craft and amateur cider makers.

What next? Dispensing Format of cider

Bag in box is an acceptable way of dispensing cider. I still think glass bottles are going to be the high-end acceptable presentation of craft ciders – I can’t see any other option in the short or long term.

What about the product?

We hear a lot about flavoured ciders. Mainstream cider makers have gone into this in a big way because it has given them a new market share (the Alco pop market under a different name). That is the point – we have been there before – that had a peak and then it disappeared. People in the long run are not going to be enamoured with fruity, hop flavoured chilli and chocolate flavoured ciders – at the end they don’t tell you anything they are just a gimmick. They are expensive as they have to pay main line duty not cider duty. I don’t think the impact will be great I think they will just fade away. We have the draft cider, which comes out in bag and bottle. With the backstory of where it was made, who made it, what apples were used in it? Compared to Australia and the US we are limited by the concept of what our pricing structure should be. It has always been a cheap drink and even our high-end ciders are relatively very cheap. I don’t see how we in the UK can follow the US where they have been able to charge $20-30 dollars for a 750 ml bottle of cider.

Questions

Are good ciders being produced in the USA or are many low quality?

Some are made with concentrate with lots of sugar but there are some very good high-end ciders as well, particularly in New England where they have been doing it for years. Examples include Farnum Hill and West County; they have some very good 750ml wine bottle sized lightly carbonated and quite dry. Some of these are made from local heritage apples

Is it possible to send English cider varieties to the USA?

You have to go through the USDA. I do know a cider grower in Wisconsin who had managed to import a range of Perry pear varieties through the USDA quarantine system. It’s taken him ten years. It isn’t a problem getting the scions into the US but they have to go through the quarantine system first. The USDA will take charge of it. They will check for viruses and will even start the process of cleaning them up (2-3 cycles). If it is too virus ridden they will get rid of it. If you are lucky they will release them after 6-10 years. It is possible with persistency and finding the right people in the USDA to help. You need a willing American recipient you would otherwise find it difficult to sell varieties into the US. It is hard to but doable. Some UK varieties in the US (eg Foxwhelp and Tremletts Bitter) are misnamed and may be just the rootstocks that outgrew dead scion wood!

What is the role of tannins in cider making?

The tannin provides the structure, the body and astringency associated with a good craft cider. They play a part in maturation so it may be months before the cider develops properly.

Some fruit need to be processed on the day that you pick them. It’s one of those areas where you have really got to know your fruit. If you don’t know already you have to learn about it ‘on the hoof’ before you know what works for you. Also that’s why Perry making from Perry pears is very frightening.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the Eden Project for their assistance in relation to put on this event.

@ Andrew Ormerod 2018